Against the backdrop of the war in Ukraine and the Middle East crisis, the symposium "Schicksalsgemeinschaft – Verlorener Frieden in Europa" ("Community of Fate – Lost Peace in Europe") organized by the Foundations of Sparkasse Leipzig examined German and European options for action.

Leipzig, 8 October 2024. With a symposium entitled "Schicksalsgemeinschaft - Verlorener Frieden in Europa" ("Community of Fate - Lost Peace in Europe"), the Foundations of Sparkasse Leipzig addressed the debate about Europe's future viability. On the eve of the 35th anniversary of the first major demonstrations in Leipzig 1989, but especially in the third year of the war in Ukraine, Dr Harald Langenfeld, Chairman of the Board of Media Foundation and of Sparkasse Leipzig, pointed to the growing war weariness in European society: "After initial solidarity with Ukraine, European unity quickly showed cracks, and the belief that not only Ukraine, but also our values and our freedom, were being defended here, is encountering declining approval and willingness to pay." At the same time, he added, external media attacks are endangering democratic discourse and contributing to the division of society. The symposium aims to contribute to "pointing out threats early on, identifying causes, and combating them." It is important to preserve "Europe as a shared space of trust": "And in this sense, a community of values that does not close itself off, but rather, as an open society, offers democracy and freedom of expression, diversity, and peaceful coexistence," said Dr Langenfeld.

In his keynote speech "Europe as a Community of Destiny? On the Political Use of History" Professor Sir Christopher Clark, Regius Professor of History at the University of Cambridge, explained how a shared European history is repeatedly nationalized retrospectively: "The complex European past is used as a fuel for national narratives." This can be seen in the Europe-wide political unrest of 1848 as well as in the national explanatory models for the outbreak of World War I. The latter, for example, also served as arguments for Britain's withdrawal from the EU. According to Clark, Russian President Vladimir Putin and his propaganda machine also regularly use historical narratives. It should be noted that Russia has returned from the revolutionary view of history of the 20th century to a philosophy rooted in the 18th and 19th centuries, which sees the country as a conservative counterpart to the liberal West. In this respect, the 20th century should be understood as an exception - in the meantime, we have returned to the "normal case" of the Petersburg Manifesto under Tsar Nicholas I, according to which Russia negotiates with major powers and regards smaller states at best as negotiable territories.

Professor Sönke Neitzel, Professor of Military History / Cultural History of Violence at the University of Potsdam, echoed this view in his contribution "The Military Capability of the Bundeswehr": The fact that smaller states have their own voice is an achievement of the 20th century and, in particular, of the European unification process. The Ukraine War, he argued, represents a "systemic conflict" between liberalism and totalitarianism. Against this background, one must ask the extent to which Europe and its nation states are capable of reform. The Bundeswehr reforms initiated since the beginning of the Russian war of aggression are concerning in this regard: "We have marched from the turning point to the braking point," he stated. To tackle genuine reforms, "politicians must also be brave and take risks." At the same time, Neitzel called for greater honesty from the generals and - as is customary in other ministries - for a scientific advisory board for the Ministry of Defense: "We need more publicity on the really big issues," said the military historian.

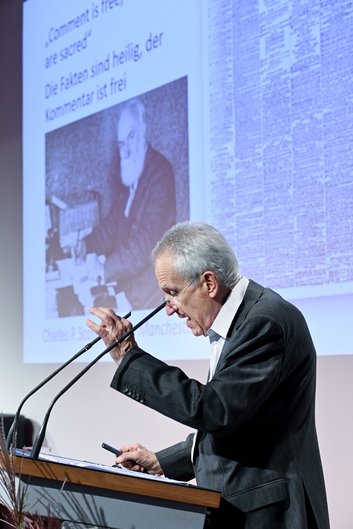

Professor (ret.) Michael Haller, formerly Professor of General and Specialized Journalism at the University of Leipzig and Scientific Director of the European Institute for Journalism and Communication Research (EIJC) in Leipzig, gave a lecture on "The Media in War." He explained that the outbreak of the war in Ukraine, as well as Hamas's attack on Israel on 7 October 2023, had brought with it an increased need for information among the German population and an increased use of news media. Media regularly face the question of who has the interpretive authority in war reporting – the military or the journalists. "It's a question that only arises in democratic states," he clarified: dictatorships are not interested in intersubjective reporting, but in propaganda. This also affects those not involved in the war and is – as in the case of the Ukraine war – difficult to contain: "The few fact-checkers act like Don Quixote fighting windmills." The public media and their network of correspondents therefore have the special task of working fact-oriented and classifying these facts. However, objectivity is limited: the media are embedded in the framework of liberal-democratic values of German society. This makes them, to a certain extent, "fellow fighters who defend our values against evil." Against this backdrop, one must continually clarify the essentials of journalistic work.

Sabine Adler, Deutschland Radio's Eastern Europe correspondent and 2024 laureate of the Prize for the Freedom and Future of the Media, highlighted the difficulty of the foreign correspondent's job in crisis zones in the concluding panel discussion moderated by Wiebke Binder (ARD and MDR public broadcasting). In the Ukraine war, she emphasized: "We have disinformation on one side, restrictions on the other. And we are not allowed into the war zone," she explained. "The 'press' emblem is a target in a war zone." In current discussions about a lack of diplomacy and peace negotiations, she felt the question of how a more peaceful situation can not only be established but also secured in the long term was missing. Marika Linntam, Ambassador of the Republic of Estonia to the Federal Republic of Germany, expressed appreciation for Germany's role in the Ukraine war: "Despite all the criticism within Germany, we are grateful that something is happening in Germany." The Baltic states have seen how their Russian neighbor has become progressively more aggressive over the past 30 years. It is therefore all the more "existentially important" that Ukraine wins the conflict and restores its regional integrity, "so that Russia does not draw the wrong conclusions."

To be permanently defensive, Europe needs a common foreign and security policy, emphasized Major General (ret.) Michael A. Hochwart, Commander of the Bundeswehr Army Training Command in Leipzig until 30 September 2024. Within such a framework, the Bundeswehr could also be reformed, he stated, but doubted that "process-oriented centralism" would achieve this goal.

"If our policies are too closely aligned with the current presumed will of the people, let us emphasize again and again that we also have our own opinion," concluded Stephan Seeger, Director Foundations of Sparkasse Leipzig: "We have no populist solutions to offer that promise quick peace and thus the calming of the people's soul – but reality. And history!"

About the Symposium

In 2018, the Foundations of Sparkasse Leipzig hosted a symposium in Leipzig entitled "Schicksalsgemeinschaft - Europas Zukunft hundert Jahre nach dem ersten Weltkriegsende" ("Community of Destiny - Europe's Future One Hundred Years After the End of the First World War"). Among other things, the question was raised as to whether, after the experiences of two world wars, a war in the Europe of the future still seems conceivable.

Six years later, and with the knowledge of Russia's war of aggression against Ukraine "richer," this question was taken up again under the theme "Schicksalsgemeinschaft - Verlorener Frieden in Europa" ("Community of Fate - Lost Peace in Europe").